The Road So Far: Jesse Lott & Travis Whitfield” at Station Museum of Contemporary Art

+5

+5 The Road So Far: Jesse Lott & Travis Whitfield” at Station Museum of Contemporary Art

The Road So Far: Jesse Lott & Travis Whitfield” at Station Museum of Contemporary Art

The Road So Far: Jesse Lott & Travis Whitfield” at Station Museum of Contemporary Art

The Road So Far: Jesse Lott & Travis Whitfield” at Station Museum of Contemporary Art

The Road So Far: Jesse Lott & Travis Whitfield” at Station Museum of Contemporary Art

The Road So Far: Jesse Lott & Travis Whitfield” at Station Museum of Contemporary Art

The Road So Far: Jesse Lott & Travis Whitfield” at Station Museum of Contemporary Art

The Road So Far: Jesse Lott & Travis Whitfield” at Station Museum of Contemporary Art

Station Museum of Contemporary Art extended its exhibition “The Road So Far: Jesse Lott & Travis Whitfield” through September 5, 2021. You have more time to see Houston artist Jesse Lott’s intricate sculptures and drawings, and Louisiana artist Travis Whitfield’s installation of a full size southern style shotgun house filled with domestic objects and photographs.

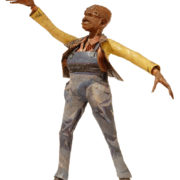

The sculptures at Station gave me a handle on why Jesse Lott associates the term “urban frontier” with his art. His sculptural components are discarded objects and pieces of trash he finds around his home in Houston’s Fifth Ward. They come directly out of the urban environment. He combines the objects however in a way that’s eye catching and memorable, and causes you to forget you’re looking at trash. This is particularly true of his figurative metal pieces. Lott told an audience at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston that his artistic materials make sense because of his Louisiana birthplace. “The logic of the material is from being raised in the country. The rural parts of Louisiana. If you needed something you couldn’t go to the store and buy it. You had to find it or make it.”

Lott’s interest in fluid linear patterns is evident at Station, in his three-dimensional metal figures and in his elegant ink drawings. Station’s outstanding presentation of curly-metal sculptural figures in proximity to curly-line ink drawings demonstrates this. Lott said, “Line moves around, crosses back on itself, becomes shape and starts to resemble something called image, or the illusion of form.”

Apart from being grounded in the urban environment, Lott frames his art as community-building. He said when he hires a kid to dismantle a discarded bedspring, one less kid becomes a juvenile delinquent that day. Lott’s community involvement however goes beyond his own art making. He teaches and mentors, and was one of the original co-founders of Project Row Houses.

In a high-gloss representation of the urban environment, a downtown Houston high rise office building, Lott experienced an absurd moment. Artist Cressandra Thibodeaux caught on video Lott being refused admission to the building’s lobby in which his art was displayed. The building’s security people, it seems, mistook the dude wearing blue overalls who asked where the food was, for a street person. While art show organizers scrambled to address the fracas, video captured the building manager’s mortified expression.

Jesse Lott (b. 1943) was born in Simmesport, Louisiana, a place he calls “swamp country.” He was raised in Houston’s Fifth Ward. He sold his first painting when he was 14 years old, and went on to study at the Hampton Institute and Otis College of Art. The artist has numerous solo and group exhibitions of sculptures, collages and drawings under his belt. In 2016 Art League Houston honored him with a Lifetime Achievement Award, and Lott was recently named the Texas State Three-dimensional Artist for 2022.

Born and raised in rural northeast Texas in “primitive conditions,” a real country boy, Travis Whitfield (b. 1945) completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at the University of Houston in 1968, studied lithography at Tamarind Institute in New Mexico, and practiced studio art in Louisiana, specializing in watercolors. In 1969 while driving through tiny Keachi Louisiana, Whitfield befriended “the porch crew,” a group of retired share croppers who hung out on the porch of a shuttered 1840s store. Through the years he photographed, painted and audio recorded these guys. They are dead, their houses are gone, their world wiped out. There is no one left who lived through the 1920s and 1930s, hauled water from an outside well, never learned to read and write, grew all the food they ate. At Station, Whitfield presents a shotgun house with furnishings, clothes line, string mop, fly swatter, as well as photos and audio recordings that document what he considers to be an important lost culture.

He took hundreds of photographs. Some photographic prints are displayed inside the shotgun house. Most images though appear on a video, which includes the recorded audio, Whitfield’s narration and a musical sound track, “got mah mojo workin.” The camera captures frost covered grass in the morning, cows, you see a watermelon harvest, a horse being shoed, wood chopping, a chicken yard, even a holy roller dunking-type baptism in a Caddo Parish lake. And the men’s faces. Whitfield said it took a few years before they trusted him enough to pose. He said he was trying to preserve their memory, and pay homage. He believes God brought him to that place in 1969.

In 1972 Whitfield began to audio-record the guys. Their carryings-on are priceless. They argue and berate. “You ain’t never gonna amount to nothing,” and he “acted da fool.” They reminisce about events they lived through, with historical interpretations, like the reason the white people elected Huey P. Long. More rattled assertions, Huey Long built a gold bridge, are challenged. “Shee-it.” Gold bridge? “Shee-it.”

www.stationmuseum.com