Think of Them as Spaces: Brice Marden’s Drawings at the Menil Drawing Institute

+2

+2 Think of Them as Spaces: Brice Marden’s Drawings at the Menil Drawing Institute

Brice Marden, “Post and Lintel 7,” 1984/2019. Graphite and wax on paper, 22 ½ × 30 in. (57.2 × 76.2 cm). Collection of the artist. © Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo Bill Jacobson.

Brice Marden, “Post and Lintel 7,” 1984/2019. Graphite and wax on paper, 22 ½ × 30 in. (57.2 × 76.2 cm). Collection of the artist. © Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo Bill Jacobson.

Think of Them as Spaces: Brice Marden’s Drawings at the Menil Drawing Institute

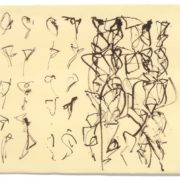

Brice Marden, “Cold Mountain Study (13),” 1988-91, Ink on Paper, 7 7/8 x 9 3/8 in. (20 x 23.8 cm), Collection of the artist. © Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Bill Jacobson

Brice Marden, “Cold Mountain Study (13),” 1988-91, Ink on Paper, 7 7/8 x 9 3/8 in. (20 x 23.8 cm), Collection of the artist. © Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Bill Jacobson

Think of Them as Spaces: Brice Marden’s Drawings at the Menil Drawing Institute

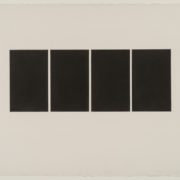

Brice Marden, “Study for The Seasons,” 1975. Graphite and wax on paper, 22 x 29 ½ in. (55.9 x 74.9 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston. © Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Paul Hester.

Brice Marden, “Study for The Seasons,” 1975. Graphite and wax on paper, 22 x 29 ½ in. (55.9 x 74.9 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston. © Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Paul Hester.

Think of Them as Spaces: Brice Marden’s Drawings at the Menil Drawing Institute

Brice Marden, “Post and Lintel 7,” 1984/2019. Graphite and wax on paper, 22 ½ × 30 in. (57.2 × 76.2 cm). Collection of the artist. © Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo Bill Jacobson.

Brice Marden, “Post and Lintel 7,” 1984/2019. Graphite and wax on paper, 22 ½ × 30 in. (57.2 × 76.2 cm). Collection of the artist. © Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo Bill Jacobson.

Think of Them as Spaces: Brice Marden’s Drawings at the Menil Drawing Institute

Brice Marden, “15 × 15 12,” 2015–17. Ink and colored ink on paper, 20 × 15 in. (50.8 × 381 cm). Collection of the artist. © 2020 Brice Marden / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Brice Marden, “15 × 15 12,” 2015–17. Ink and colored ink on paper, 20 × 15 in. (50.8 × 38.1 cm). Collection of the artist.

By Virginia Billeaud Anderson

Brice Marden is as handsome as he was decades ago when he was plagued by female predators. Decked out in an expensive black sports coat and his black wool cap, he looked especially bad-ass at the dinner for his Menil drawing exhibition. It was a high-fallutin dinner. Papercity mag published a picture of the linen covered banquet table with lovely floral arrangements and gold gala-style banquet chairs. Marden sat next to Menil Board of Trustees Chair Emerita, Louisa Stude Sarofim.

The big daddy of the modernist tradition spoke about his art at the Menil. Here are a few notes on Marden’s drawings and his paintings.

One thing he said argued well for ranking an artist’s words over mouthy art critical analysis. Architectural details from antiquity, Marden clarified, did not directly inspire the “Post and Lintel” drawing series, one of six series in the exhibition. “People have said they relate to, you know, I go to Greece every summer, so they made it as though it’s based on ancient Greek architecture, and these things are around, these kind of influences are around, and maybe, they were based on, ha ha, ancient Greece, but I wasn’t thinking about that.”

Marden gave his Menil talk on February 21. A few weeks later the bloody virus slammed the doors on his drawing exhibition. Fortunately, the Menil re-opened in mid-September. You have until October 11, 2020 to see “Think of Them as Spaces: Brice Marden’s Drawings” at the Menil Drawing Institute.

The virus didn’t stop collectors from hankering after his stuff. Less than two months after the Menil locked-down, Marden’s “Window Study No. 4” (1985) fetched $1.1 million at Sotheby’s New York, in the auction house’s first ever online day sale of Contemporary Art. Comparatively, it was a puny amount. “Window Study No. 4” was a preparatory study for the commission to design the windows that lined the apse of Basel Cathedral, and doesn’t seem to be one of his “major” paintings. On July 10, however, Christie’s Auction sold the two panel “Complements” (2004-2007) for $30.9 million in their virtual sale. Try to imagine a record breaking auction sale without the verbal antics of the auctioneer, or the squirming, sputtering, occasional yelling like drunks in a sports bar, of the rich collectors and their proxies.

“I work a lot that way, uh, one after another after another after another, they (drawings) stay together, they come from a certain time or place.” Assistant Curator Kelly Montana who organized the exhibition is projecting slides of the “Mirabelle Addendum” drawing series, another series in the exhibition. Marden is essentially describing his career long practice of making drawings. He told a background story. When his first daughter Mirabelle was born, he handled her two a.m. feedings. He placed a rocking chair, a step ladder and a drawing pad (Indian ink paper) in a closet. “I would hold her, you know, like the football grip, and I drew these drawings.”

Marden revealed an unexpected aspect of commercial strategy. His gallery people produce facsimile reproductions of the drawings, just like a Leonardo, or the Book of Kells.

He will be 82 in October. In that it can take years to bring a painting series from the preliminary drawing stage to completion, one could say he’s running out of time. He said this in 2017 when he left the Matthew Marks Gallery to sign with Gagosian. “I’m running out of time.” Even before he underwent chemotherapy treatment for cancer, he admitted to hunkering down when his brother’s unexpected death brought home his own mortality. “You got to get serious, it’s harder to work when you’re old, you know what I mean, you gotta climb up a ladder all the time.” At the Menil, Marden announced he is beginning new work. “I’m still sort of hacking away at it, I mean I’ve got 4 paintings I’m just starting and I keep thinking I want more intuition, I want to get some human thing out there, uh, you know, you gotta do it, ha ha, gotta give it a try.”

He first discussed the graphite and beeswax series created as studies for “The Seasons” (1975), a multi panel painting in the Menil’s permanent collection. It was interesting to learn how directly nature inspired the colors. In 1975, Mrs. de Menil put “The Seasons” in a Rice University show that included paintings by David Novros and Rothko. Just before opening, Marden told her he was unhappy with its colors. No problem, she assured him, he could re-paint them after the show. Following the opening, Marden and Novros high-tailed it through the Southwest, “a driving trip,” to visit places like Chaco Canyon, where he encountered unfamiliar colors in nature, cottonwood trees for instance. When he returned to Houston to re-paint, they entered his palette. This wasn’t the first time Marden told this story, in a previous telling, Mrs. de Menil disliked the revised painting. “But she kept it.”

His story brings home the fact that close observation of landscape plays an integral role. Consider “Grove Group I” (1972-73) in MOMA’s collection. Abstraction captures the essence of the blueish greenish grayish tones of olive trees he knew in Greece.

Arguably, this period of the 1970s cemented Marden’s commitment to the Abstract Expressionist tradition. He looked closely at Rothko’s expanses of color, handling of luminosity, scale and grouping. He floated monochromatic oil paint into wax for luminescence. Beauty mattered.

In about 1941, Henry Miller wrote that the Greek island of Hydra is a rock which rises out of the sea like a huge loaf of petrified bread. It is a living rock, Miller said, a divine wave of energy suspended in time and space. Whichever god created Hydra, he added, was an expert calligrapher. How interesting that Marden, who has owned a home on Hydra since 1973, told a Tate Modern lecture audience that energies move through the earth. “The energy of how Hydra just came up out of the earth, those energies are so exciting and powerful.” Marden said he tries to capture that energy in his painting, although it is easier to get the energy into a drawing, because drawing is more immediate.

“When I did the Cold Mountain paintings, I was reading the Cold Mountain poems.” The Menil talk now focuses on the “Cold Mountain Studies” which curator Montana said represent “a seismic shift” in Marden’s career. He changed from monochromatic painting to fluid calligraphic mark-making. People wondered if it was dumb to change direction away from a commercially successful style. Reinvent?

Legend holds the 8th or 9th century Tang Dynasty poet Han Shan, whose name translates to “Cold Mountain” wrote the “Cold Mountain” poems. American poet and Zen scholar Gary Snyder, who has a fondness for boil-makers, translated the poems. Inspired by their poetic associations – mountain trails, boulders, trees, moss, clouds – as well as Japanese calligraphy exhibitions, Marden laid down ink glyph-like markings in the spaced-apart columnar format of ancient calligraphy. From these frameworks, he intuitively overlapped squiggly lines. Where dense areas needed “correcting,” he applied white, to erase and reduce, suggest depth, then re-entered to build up. After a year or two, he felt confident he could make paintings with the same complexity and fluidity as these gestural drawings

The first painting completed from the Cold Mountain studies was essentially black and white in the manner of a calligraphic hand scroll, except for gray areas where black paint was thinned or mixed with white primer. Others had sinuous lines looped over the columnar underpinning. All too soon there was color. Marden ultimately abandoned the grid for spontaneous all-over loops. Pollock territory! In the style of Pollock, his image emerged from the painting, floated out of it as if discovered instead of applied to the surface.

Changing directions wasn’t dumb. Collectors and major museums pounced on the lyrical abstractions. There were insane auction sales. He even dipped back into shimmering monochromes. In 2006 Peter Schjeldahl (New Yorker mag) called Marden the most profound abstract painter of the past four decades.

The Menil exhibited some of the Cold Mountain drawings in 1992-93.

More than any other series in the exhibition, “15 x 15 (1-15)” (2015-2017) demonstrates the benefit of listening to an artist’s words. He began these drawings by making 15 marks across the sheet. Their entangled black skeins and vibrantly colored ribbons over patches of translucent white are so dense, though, it’s impossible to discern their compositional substructure. Exuberant gestural flourishes eviscerated it. Programmatic and intuitive in equal measure, the drawings seem to have perfect compositional balance. If Marden doesn’t run out of time, the 15 x 15 series will become paintings. “These are basically studies for the paintings that I’m just about ready to start in the studio.”

Marden sketches while traveling, China, wherever. And he sketches at his homes, in Greece, New York, the Hudson River Valley, the Caribbean. He doesn’t try to duplicate, he tries to capture an essence.

Not every drawing is a preparatory study for a painting. Marden believes every drawing is finished, and holds its own as an artwork.

What’s the best way to view a drawing? Intimately. Get as close as possible, get right on top of it, “which gets you back to the experience of it being made. People say, you know about my stuff, I don’t know what to look for, and I say, just pick a line and follow it and hopefully, you begin to disappear, or you begin to, uh, you know. So that’s my suggestion about looking at drawings.”